News

Stephen Tall, the EEF’s director of development and communications, unpicks six of the key findings from the EEF report on the attainment gap, explaining what the data tells us about the difference in attainment between disadvantaged students and their classmates.

Today, the EEF is publishing a report analysing the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their classmates. The reason why is simple. If we want to tackle the challenge of this gap, we have to understand it – both its scale and nature, as well as the factors most likely to help close it.

Our report assesses the attainment gap through the lens, first, of children and young people; and secondly, of schools, as well as early years and post-16 settings. It highlights and summarises what we believe to be the key issues, and how our analysis of them informs our practical work with teachers and senior leaders.

Here are six of the key findings:

1. There will be little or no headway in closing the attainment gap in the next 5 years – but there is still an opportunity for secondary schools to make a difference.

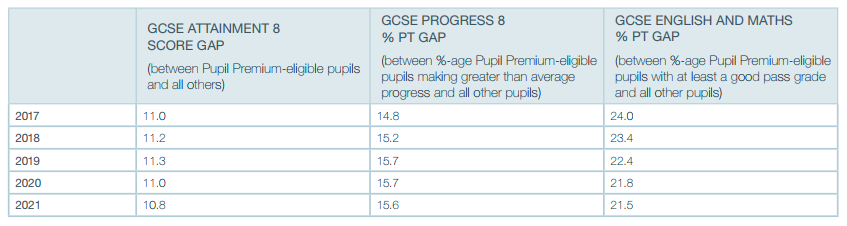

The correlation between pupil outcomes at Key Stages 2 and 4 allows us to forecast the national attainment gap up to 2021. This suggests that, as it stands, the gap in Attainment 8 – which measures average achievement in GCSE across eight subjects – of c.11 points between disadvantaged pupils and their classmates will remain essentially unchanged from 2017 to 2021. Crucially, however, there is opportunity for secondary schools to help reduce this gap. If disadvantaged pupils were entered for the same number of subjects as all other pupils, the Attainment 8 score gap would close by about 2 points – for 2021, this would reduce the gap from 10.8 to 8.8, a significant reduction.

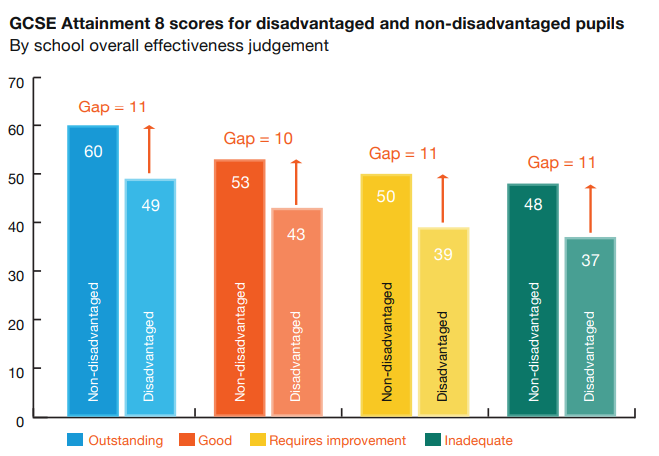

2. The attainment gap is consistent across all types of schools, regardless of their Ofsted rating.

While GCSE grades for all pupils are higher in schools with Ofsted ratings of ‘Outstanding’ or ‘Good’ than in those rated ‘Requires improvement’ or ‘Inadequate’, the size of the Attainment 8 gap is consistent across all four types of schools. So, while wanting more schools to achieve a Good/Outstanding rating from Ofsted is itself a valid aim – after all, absolute attainment levels for all pupils in ‘Outstanding’ and ‘Good’-rated schools is higher – it is not in itself sufficient to close the attainment gap.

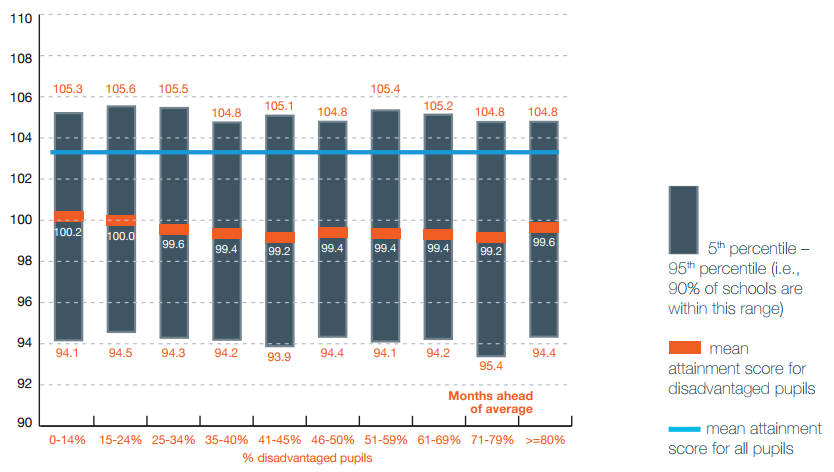

3. There are 1,726 primary schools in England – 10% of all primaries – where disadvantaged pupils at Key Stage 2 attain above the national average scaled score for all 11 year-olds.

These schools are spread across the spectrum of disadvantage, with 72% of them having an above-average proportion of disadvantaged pupils. More than 70% are outside London. There are a similar proportion of secondary schools in England – 8% of all secondaries (272 schools) – where disadvantaged pupils at GCSE perform above the national Attainment 8 score for all 16 year-olds. This suggests it is possible to close the attainment gap – if we can find effective ways to learn from the successes of the best-performing schools, and achieve greater consistency between similar schools. The EEF’s Families of Schools database is one practical tool designed to enable individual schools to do just that.

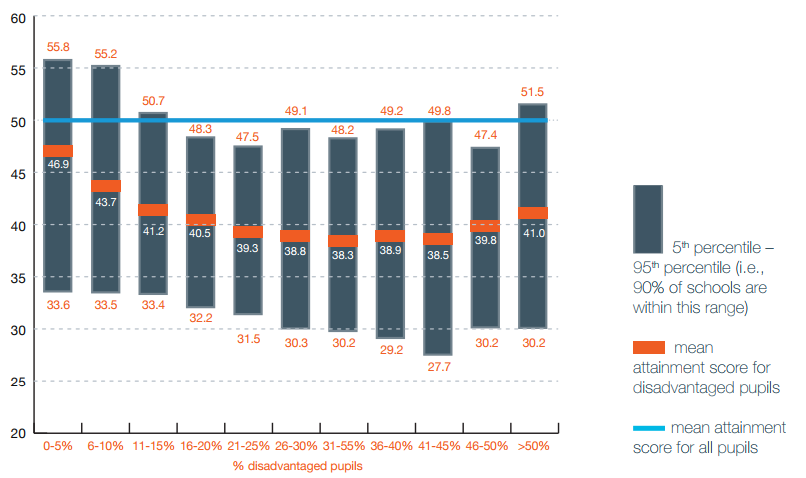

4. There is huge variability in outcomes for disadvantaged pupils between schools with similar levels of disadvantaged pupils.

For example, there are schools with 41-45% of disadvantaged pupils where those pupils achieve an Attainment 8 score of 27.7 (equivalent to 5 D-grades at GCSE, including English and Maths); and schools with similar levels of disadvantaged pupils where they achieve a score of 49.8 (equivalent to 8 C-grades at GCSE, including English and Maths). Though it might be tempting to expect all schools to be as good as the best performing, there is a more realistic initial goal to work towards. That is for schools with below-average outcomes for their disadvantaged pupils to reach at least the average attainment levels for schools with similar levels of disadvantage to them. In secondary schools with 26%-30% disadvantaged pupils, for instance, this would mean moving from an Attainment 8 score of 30.2 to the average of 38.8. Doing so, would boost an individual student’s GCSEs by around one grade in most of their Attainment 8 subjects.

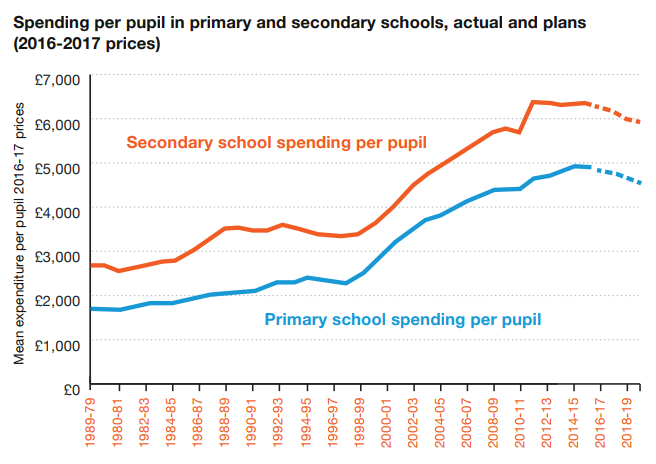

5. While a good level of funding for schools is important for a range of reasons – and some research suggests is particularly beneficial for disadvantaged students – there does not appear to be a direct and straightforward relationship between increased school funding and increased pupil attainment.

Public spending per pupil in real terms has more than doubled in both primary and secondary schools over the past 40 years, with much of that increase concentrated in the period 1999-2012. It is much less clear that there has been a similar increase in attainment outcomes for pupils over that period. What matters most is how schools can effectively and efficiently use the resources they have (both financial and human) for maximum impact.

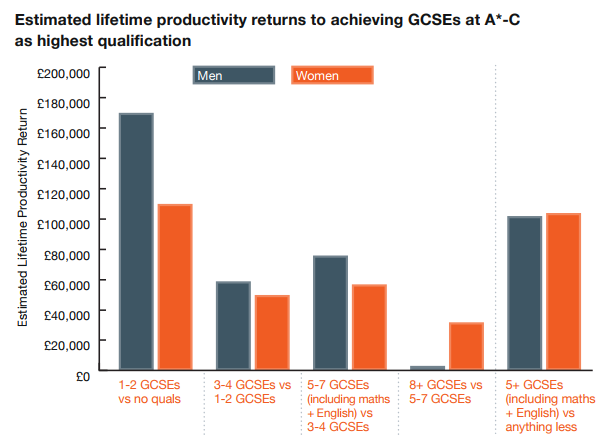

6. Even small improvements in young people’s GCSE qualifications yield significant increases in their lifetime productivity returns and in national wealth – highlighting the importance of continuing to focus on improving results for currently low-attaining pupils.

A report from the Department for Education highlights that individuals who achieve 5+ good GCSEs including English and maths as their highest qualification, have estimated lifetime productivity returns in excess of £100,000, compared to those with below level 2 or no qualifications. Even achieving very low levels of qualification – just one or two GCSE passes compared to no qualifications – is associated with large economic gains.

You can read the report in full here.

Sources for charts above:

- Bespoke analysis by Education Datalab for the EEF.

- Chart supplied to EEF by Ofsted (September 2017)

- Bespoke analysis by Education Datalab for the EEF.

- Bespoke analysis by Education Datalab for the EEF.

- ‘Long-run comparisons of spending per pupil across different stages of education’, Institute for Fiscal Studies, (February 2017)

- ‘GCSEs, A levels and apprenticeships: their economic value’, Department for Education (December 2014)

This blog was originally posted by the EEF.